Bonjour dear readers,

This past week we celebrated our oldest son’s 13th birthday. I’ve been explaining to our French friends that 13 is a milestone for us because it’s the first number that has “teen” in the name, and that makes Titus a teenager (and me the dad of a teenager!). You don’t have the same thing in French, passing from douze to treize doesn’t have any particular impact.

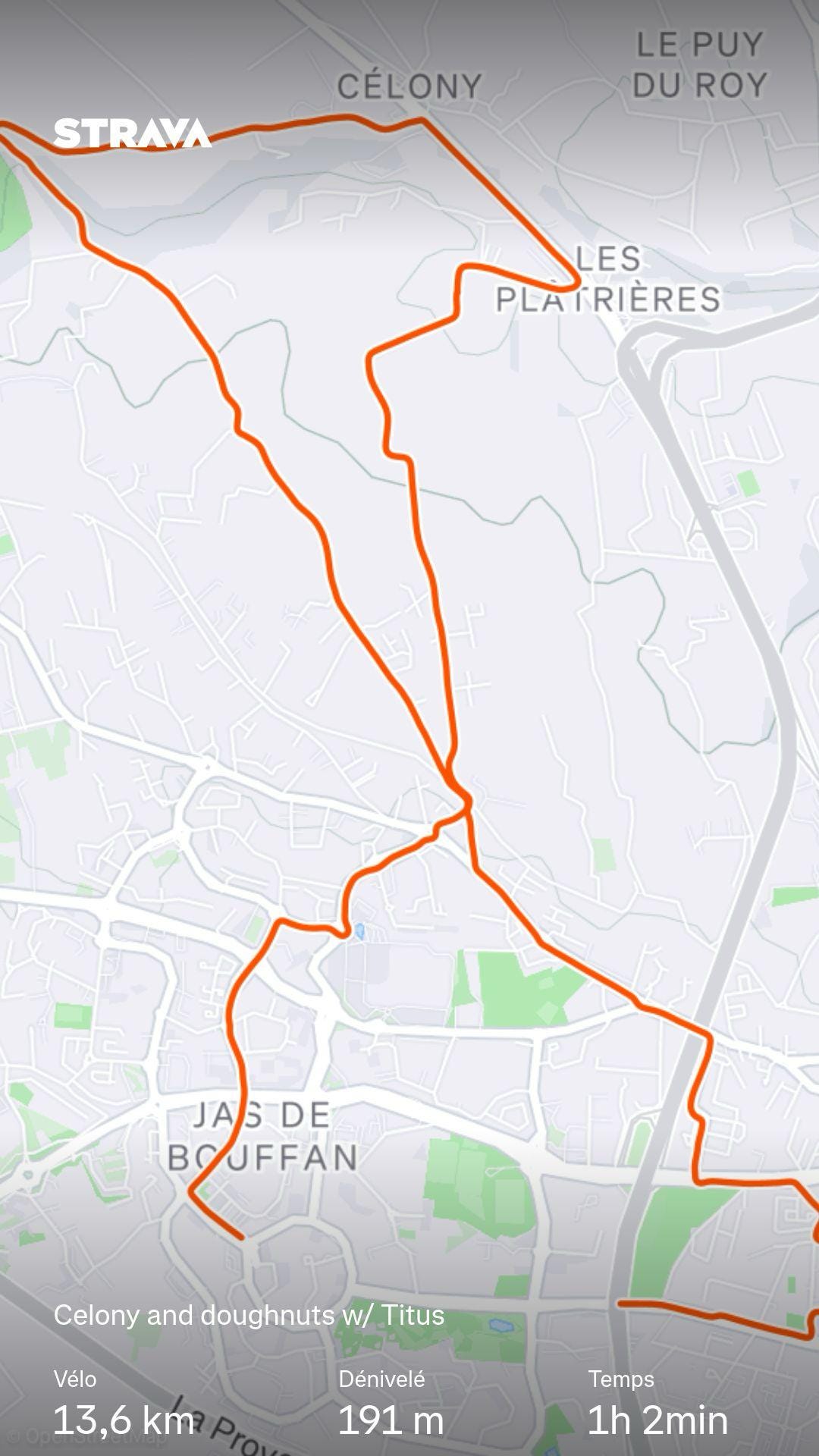

My favorite thing that we did is the bike ride that Titus and I took early Saturday morning, climbing a significant hill and finishing up at the boulangerie. Since Titus also reads this newsletter, I’m going to take this opportunity to say: Titus, I love you and I’m proud of you.

A big thank you to everyone who prayed for my presentation last night on the Bible as the Word of God. It went really well – the students were engaged and they asked a ton of good questions which made me really happy. I hope I was able to encourage them as much as they encouraged me.

Buddhism

Read Part 1: “The Bible and the first ‘Noble Truth’”

The Bible and the second “Noble Truth”

“And this, monks, is the noble truth of the origination of dukkha: the craving that makes for further becoming — accompanied by passion & delight, relishing now here & now there — i.e., craving for sensual pleasure, craving for becoming, craving for non-becoming.”1

The cause of the dukkha that inflicts us is our craving or desire. We want to have things we cannot have, and so we suffer. This causes not only suffering or dissatisfaction in this life, but also the phenomenon of rebirth, whereby we are locked into a cyclical existence marked by dukkha.

As for this craving, its root is ignorance. As Steve Hagen explains:

It’s imperative to recognize that our dissatisfaction originates within us. It arises out of our own ignorance, out of our blindness to what our situation actually is, out of our wanting Reality to be something other than what it is.2

This link between ignorance and suffering is not foreign to the biblical worldview. God exclaims through the prophet Hosea: “My people perish for lack of knowledge (Hos 4:6).” It's true that our misconceptions of the world hurt us. We have a thirst that we seek to satisfy in a host of idols, none of which can quench our thirst. And the Buddhist is right to reject these idols to which the human heart naturally turns:

What would answer the hollow ache of the heart? Money? Fame? Sex? Learning? Power? Life in the fast lane? Life in the slow lane? Luxury apartments in Paris and Manhattan? A quiet cottage by a running brook? Perhaps you can sense already that none of these specifics will do the trick. Indeed, whatever object we pick can at best only temporarily still some particular yearning. The underlying ache of the heart remains omnipresent and unquenchable.3

According to Buddhism, the reason we act as we do is because we are ignorant of the nature of reality.

Individuality

The most important aspect of this human ignorance is ignorance of our own nature. Each of us believes that he is an individual with an existence of his own, but this impression of an individual existence is denied in Buddhism. According to Hagen, “We tend to think of ourselves as persons or individuals—separate entities persisting through time. But we aren’t. What we call a person, the Buddha referred to simply as ‘stream’.”4 This understanding is an aspect of the doctrine of “dependent origination” or “conditioned co-arising.” In the words of the Buddha: “When this is, that is. From the arising of this comes the arising of that. When this isn’t, that isn’t. From the cessation of this comes the cessation of that.”5 The idea, then, is that everything that exists is in a great stream of cause and effect, where all is transient and impermanent. People have no fixed identity because they are always in the process of becoming, always the momentary result of upstream causes, always in the process of giving way to downstream reality. The human intuition of being an individual that endures in time is therefore erroneous and a source of dukkha. According to Hagen, “It’s by holding onto this notion of self—and we hold it most dear—that we live in defiance of Reality. This is the means by which we suffer, and suffer greatly. It hurts to defy Reality.”6

This teaching is so counter-intuitive that human language cannot even accommodate it.7 It's not self-evident, but rather a logical consequence of a conception of the universe without a transcendent God. When the Stream encompasses all of reality, there is no point of reference for individual people. But the transcendent God who is outside the Stream doesn't change, and he is the fixed reference point for all his creatures. He can choose to create people, and he gives them a stable identity that doesn’t depend on their constantly changing nature. It is the fact that the Transcendent is a personal God that grounds the individualized existence of other persons.

Transcendance

This Buddhist understanding of human existence has its origins in the Buddha's response to a philosophical debate of the time on the existence of the eternal soul (ātman). The Buddha's triumph was to see that the correct answer was neither “yes” nor “no”. His approach is called the “Middle Way”, and it refuses to cling to the “extremes” of human conceptions, “frozen views”, of reality.8

This idea of the Middle Way is a constant thread running through Buddhist teaching, even to the point of asserting a Middle Way between existence and non-existence.9 There's this desire to transcend the categories of our experience in this world, this intuition that truth is greater and more multifaceted than our human concepts. According to Hagen, “The world of experience simply isn’t frozen. Reality won’t be condensed into concepts.”10

This is where the absence of God really makes itself felt in the Buddhist worldview. There’s this search for the transcendent, which can never be found, because the starting point is the non-existence of the one who is the Transcendent. Where God should be, there is a blank spot on the map that can only be defined by what it isn’t. So, for example, the description of nirvana offered by the Buddha is entirely negative, a list of everything that nirvana isn’t:

Monks, there exists that sphere where there is neither earth, nor water, nor fire, nor wind; neither the sphere of infinite space, nor infinite consciousness, nor the sphere of no-thingness, nor the sphere of neither-perception-nor-non-perception; neither this world nor the other world, nor both sun and moon. And there, monks, I speak neither of coming nor of going, nor of staying, nor of falling away, nor of arising [in a new rebirth]; it is really unsupported, lacking in continued temporal existence, and objectless (Ud. 80-1).11

Transcendence can never be found because the absence of the Creator God entails the absence of the distinction between Creator and creatures, which is what really defines transcendence Not knowing the God who is the fountainhead of existence, the Buddhist correction for human ignorance ends up being just another form of ignorance.

Original Sin

By losing sight of the distinction between Creator and creature, Buddhism also loses sight of the separation between the holy God and his sinful creatures. This is the fundamental flaw in the Second Noble Truth: ignorance, which is a source of suffering, does not suffice as an explanation of the human condition. For one thing, ignorance itself needs some explanation. Where does this ignorance come from? Why do people tend to see things wrong? How did our vision get to be so corrupted? Secondly, and more importantly, there is another, deeper reason for suffering. It's just not possible to reduce all of the wickedness in human history to simple ignorance. Where does hatred come from? Where does the pleasure of hurting others come from? What explains the perversity of the human heart?

The Bible reveals what's missing from the Second Noble Truth: the concept of rebellion. Man was created for God, to find fulfillment in a relationship with his Creator, but because the first man rebelled against the Creator, human nature became corrupted to run away from the God who we still long for. It’s this corruption of the heart that is at the root of human wickedness, and it is enmity towards God that causes people to seek idols in an attempt to quench their thirst for God.

As long as the rupture between God and man is not taken into account, as long as we fail to recognize that the thirst we have is for God, we will not be able to understand the cause of dukkha. For this reason, the doctrine of original sin incorporates and surpasses the Buddhist doctrine of the cause of dukkha.

The King and I and the collision of worldviews

Chelsea and I watched The King and I recently, which was the first time either of us had seen it since we were kids. I honestly hadn’t remembered anything about it except the song “Getting to Know You,” and I was caught off guard by how good the ending is. You didn’t expect Yul Brynner to die, since he wasn’t old or sick, but once he does you realize it was inevitable. And through his death, this movie actually says something significant that we should pay attention to.

On one level, Yul Brynner died of a broken heart, or more precisely, a heart that ripped itself in two. With half of his heart he was a traditional king of Siam, proud of his own culture and his place in it. But with the other half of his heart, he wanted to be European. He was just as attached to the idea of being scientific and forward-looking as he was to traditional values and heritage. He thought that he could hold on to both of these at the same time, but the inherent contradictions led first to puzzlement (“There are times I almost think I am not sure of what I absolutely know”) and eventually to the fatal crisis when the moment of decision was forced upon him. In this moment, unable to commit to one way or the other, his heart was snapped in two.

On another level, his death is inevitable because he is the king of Old Siam, and Old Siam itself is dying. A New Siam, fundamentally different in its worldview and values, is coming into being and bringing to an end the Old Siam. Yul Brynner himself instigates this transition; he is the father of the New Siam, but he does not belong to it. He is the last king of Old Siam, and he cannot outlive his own kingdom. New Siam needs a new king, formed from youth with the values of the new worldview. Even as Yul Brynner takes his last breaths, his son begins his reign by abolishing the practice of prostrating before the king.

There’s a lesson here about the inherent coherence of worldviews. Yul Brynner wanted to import some modern science and European learning, without realizing that in so doing, he was also bringing in a fundamentally different view of human dignity and equality. He wanted his children to speak English, and what he got were children who were thinking “in English” on such questions as slavery and royalty. It turns out that worldview commitments and values do not come à la carte. Ideas are rooted in a worldview, and when you take a flower that you find attractive, you tend to get more than you bargained for.

For example, you might think you’d rather live without the God who claims authority over your sex life, but that also means doing away with the image of God that makes you anything other than an “ugly bag of mostly water”.12 Or you might think you’d prefer karma to sin, but eventually you discover that you’ve got rid of redemption as well.

In the same way, you might like this or that aspect of Jesus. You might like the Sermon on the Mount, or the way he elevated women, children, and the poor. But Jesus will not be taken à la carte. The same Jesus who said “Let the little children come unto me,” (Mt 19.14) also said, “Unless you believe that I AM, you will die in your sins” (Jn 8.24).13 We can’t go in two different directions at the same time. Either Jesus is Lord and we follow him with all our heart, or he’s not we go our own way. And either way, it’s this decision that sooner or later decides all the rest. “For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it” (Mk 8:35).

Starry Night

The amazing (and sad) story of a beloved painting. The place where he painted it is less than 50 miles from where we live.

~

And calling the crowd to him with his disciples, he said to them, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake and the gospel’s will save it. For what does it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul? For what can a man give in return for his soul?

Mark 8:34–37

“Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta: Setting the Wheel of Dhamma in Motion” (SN 56.11), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 30 November 2013, [http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn56/sn56.011.than.html](http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn56/sn56.011.than.html).

Steven Hagen, Buddhism Plain and Simple. The Practice of Being Aware Right Now, Every Day, New York, Tuttle, 2011, p. 21.

Ibid., p. 70.

Ibid., p. 52.

“Assutavā Sutta: Uninstructed (1)” (SN 12.61), translated from the Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. Access to Insight (BCBS Edition), 30 November 2013, http://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/sn/sn12/sn12.061.than.html.

Steven Hagen, op. cit., p. 139.

As Hagen admits: Ibid., p. 140.

Ibid., p. 131–136.

Tricycle, « What Is the Middle Way? », Buddhism for Beginners, https://tricycle.org/beginners/buddhism/middle-way/.

Steven Hagen, op. cit., p. 136.

Peter Harvey, Buddhism and Monotheism, Cambridge Elements: Religion and Monotheism, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2019, p. 36.

English translations typically add the word “he” not present in Greek. Cf. verse 58 and Ex. 3:14.